30th April 2020 by Jason Vincent

Lessons in Forensic Software Development – "move fast and break things, but never break them again"

Ever since Mark Zuckerberg coined the now famous motto “move fast and break things” startups around the world have embraced it, and done just that. It’s an enticing concept, particularly in a world where software teams large and small, in organisations ranging from startups to governments, have adopted an agile working methodology.

I feel, however, that this can lead to some dangerous behaviours. We’ll explore some of these here. Let’s take for example a startup creating a new concept – they’re a small team initially, and don’t have the resources to have a large development team with dedicated QA, CI pipelines, detailed service monitoring dashboards etc. At the same time they also don’t have much traction yet – they maybe have some early adopters using their product or service, but they’re still at the start of their journey to achieving mass adoption.

This is the right time to ‘just get it done’. Hack something together, test it out, get feedback, and repeat. If it breaks, chances are most people won’t notice, and if they do, they probably won’t care. They’re early adopters after all. Pioneers, using your service before anyone else, and proud of it.

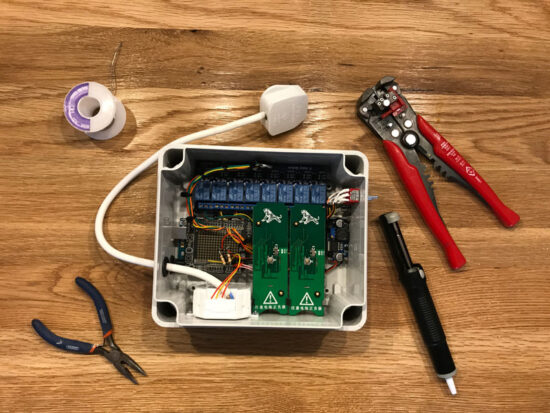

However, we need to recognise the difference between building software platforms (eg: a website or online service / mobile app), and building hardware (eg: creating a physical product you purchase and hold onto).

In an age of crowdfunding with everything from the latest intelligent drone to automated dog feeder available for pre-order, the one statistic that stands out above the rest is just how many of these projects and startups ultimately fail. Why? Partly because hardware is, well, hard. But also partly because, in my opinion, their approach can often be wrong to begin with.

If you go to a website and something breaks, you might try again later. Netflix was down for several hours a couple of days ago. It didn’t make me want to unsubscribe. However, if you purchase a physical product and it doesn’t perform the way you expect, then the level of disappointment – even frustration – is far greater.

Mobile apps sit somewhere in the middle. It’s common for an app to suddenly stop working, requiring the user to download an update for it which miraculously solves the problem. I saw this happen recently with MyFitnessPal which was frustrating, but still relatively easy to solve.

And here we arrive at the chain of difficulty in “fixing mistakes” amongst technology products:

- Online website: If it breaks, it gets patched (usually in one place). Developers are alerted to this, and usually it gets resolved quickly. The disruption to the user is simply a momentary inconvenience, and they can return later to try again. Often they won’t even be affected because it will be patched before they’re even aware.

- Mobile apps (or desktop software): If a version breaks, *everyone* with that version gets affected and will undoubtedly realise. Why? Because it means they need to download an update – a proactive action to be taken by the user (I’m glossing over new app development approaches whereby updates can be released without actually updating the app itself, as these inevitably require an internet connection etc).

- Hardware devices: If it breaks, you have a major issue on your hands. You need to issue firmware updates to each device, and hope with bated breath whether the device is ‘bricked’ or not, and will recover from whatever code abomination bob pushed to Git that day. If it doesn’t recover, you’re in for a painful set of emails and calls to customers which may be deeply apologetic. All of this can take a while, create massive inconvenience for customers, and diminish their brand loyalty. Customers can be fickle, after all.

So is “move fast and break things” really the best approach for hardware startups? I’d argue no, and strongly caution against this approach.

The starting point for any company, of course, should be tests – automated tests, unit tests, integration tests, and – perhaps most important – a final QA process of some sort by, you know, humans. Irrespective of the size of your organisation, this is essential. It will help cover some of the bases, many of the edge cases you wouldn’t think to test, and help provide backwards compatibility for older, legacy devices and features.

At Aeguana we’ve contended with these challenges for over a decade developing digital vending machines and automated retail technology. As leaders in the space we can’t afford not to innovate constantly – it’s what we do, and we love doing it. So how do we ensure we don’t break things?

For a start, we deploy cautiously. We sandbox projects, ensuring that any adverse impact is very limited. We test thoroughly. Hardware is different in so many ways. There are layers of complexity to contend with. Things could go wrong because of a software bug. Or it could be an issue with the electronics that hadn’t surfaced before. Or it could be an issue with a library or dependency on an older device that is incompatible. Or it could be unexpected user error that you simply can’t diagnose and identify. The list goes on, and it’s clear to see why businesses starting up can struggle to cover all these bases and deploy solid, reliable software.

There’s a further element that is of crucial importance when working with hardware in my opinion. Being forensic. Take the aviation industry as an example – if anything goes wrong, a thorough investigation is immediately launched. Sometimes this might seem excessive. Perhaps there was a fault, but no one was injured – does it really make sense to assign an entire team to investigate that issue/event for months? Well, yes. And that is why it’s the safest mode of transport, despite being one of the most complex and open to catastrophic failure.

The approach is actually quite simple: understand the root cause, and take the necessary steps to never let it happen again.

We try to apply this everywhere we can. Every error, every bug is logged automatically and investigated. We don’t dismiss or close down any issue without understanding a) what happened b) why did it happen and almost always c) how do we stop it ever happening again. Sometimes this takes a few hours from start to finish. Often it takes days. On occasions it takes weeks. But once these three criteria have been answered, we’ve not only improved our technology, we’ve improved our knowledge. By sharing this knowledge, we can prevent it happening again.

But there’s another side to this. Allowing enough time. We believe in trying to build things right the first time. Avoid cutting corners, and empower the team to create the best products and technology they possibly can. The stronger your starting point – your foundation – the better the chances of minimising problems later down the line, and the easier they will likely be to resolve if they do emerge. And when there is an issue to resolve, we then adopt this same approach – fix it right the first time. Not only should it not be ignored, it should be fully understood and resolved, without resorting to temporary patches.

By preventing it happening again, we’re undertaking constant improvement, whilst allowing ourselves to innovate at the same time. Yes, things may break, and yes, we do still move fast. But by being forensic and learning from every mistake we can deliver the level of quality and resilience our clients have come to expect.

Keep innovating. Keep learning. And always keep improving.

Photo by ThisIsEngineering from Pexels